Imperialism – The policy of extending a country’s power and influence through diplomacy or military force, often for economic gain.

Communism – A political and economic ideology advocating for collective ownership of resources and the abolition of class distinctions.

Capitalism – An economic system in which private individuals or corporations own the means of production and operate for profit.

Sovereign – The authority of a state to govern itself without external interference.

Machinations – Complex and often deceitful schemes designed to achieve a particular goal, usually in politics.

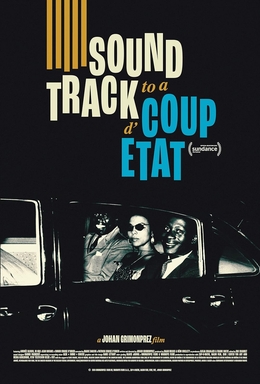

I begin this article with definitions because these terms—imperialism, communism, capitalism, sovereignty, and machinations—are central to Soundtrack to a Coup d’État. Throughout the film, these concepts appear repeatedly. Understanding these terms before watching the documentary—or even reading this review—is crucial. Without them, it is easy to miss the depth of what the film is revealing. Soundtrack to a Coup d’État is not just about history; it is about power—who wields it, who loses it, and how music, politics, and deception have been used to control the fate of nations.

If you grew up in Kenya like I did—or anywhere in Africa—you were likely taught a version of history that barely scratched the surface. Yes, we learned about colonialism, but only as a story of oppression followed by heroic resistance. What we weren’t taught was the depth of foreign interference that continued long after independence, shaping our economies, politics, and even the art we consume today.

The film is made by Johan Grimonprez. He is from Belgium, the same country that colonized Congo—a fact that immediately made me skeptical. Too often, Western filmmakers take African stories and distort them, centering their own perspectives while glossing over the deeper truths. But Soundtrack to a Coup d’État surprised me .The depth of history, the brutal honesty about Belgium’s role in Lumumba’s assassination, and the intricate web of Cold War politics laid bare in the film felt different. Grimonprez does not sanitize or simplify—he presents a well-researched, unflinching look at how Africa was used as a chessboard by global superpowers. The inspiration to make the film is actually kinda funny. It was his fascination with Nikita Krushchev’s shoe-banging incident. The film is entirely made with archival footage with a few interviews here and there.

Many of us never learned about Patrice Lumumba beyond a brief mention in school( I actually thought he might have been from senegal), yet his assassination was one of the most pivotal events in African history. We were told that African leaders like Kwame Nkrumah and Thomas Sankara had radical ideas, but we weren’t taught how Western powers conspired to bring them down. We were taught that the Cold War was a conflict between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, but we weren’t told that Africa was one of its biggest battlefields, where coups were orchestrated, leaders were eliminated, and entire nations were destabilized to serve the interests of foreign powers. We were taught that the UN was to help bring peace but we weren’t taught how much it contributed to chaos in Congo.

And then there’s jazz. Most of us associate it with African American culture, but how many of us knew that jazz was used as a political tool to mask U.S. imperialism? How many knew that Louis Armstrong, one of the greatest musicians of all time, unknowingly became a pawn in the CIA’s propaganda machine? How many even knew that the U.S was involved in Africa’s colonialism? This is the brilliance of Soundtrack to a Coup d’État—it doesn’t just tell a story; it forces us to rethink everything we thought we knew.

Johan Grimonprez’s film dissects the events leading to the 1961 assassination of Patrice Lumumba, the first democratically elected prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Lumumba’s crime was simple: he wanted true sovereignty for his country. But sovereignty is dangerous when it threatens global capitalism. The same Western powers that once colonized Africa could not allow an African leader to succeed without their influence. So, they did what they had done before—and would do again. The popular divide and conquer method. They had him arrested, tortured, and eventually executed. The film makes it clear: Lumumba did not just die. He was eliminated.

Uranium, a key ingredient in the atomic bombs that reshaped history, was mined from Congo—one of the many reasons Belgium was so desperate to maintain control. Soundtrack to a Coup d’État reminds us that this exploitation never really ended. Grimonprez includes ads for Teslas and iPhones, subtly linking the past to the present. Just as uranium fueled the nuclear age, Congo’s vast mineral wealth—now in the form of cobalt and coltan—powers the devices we can’t live without. The faces of the oppressors may have changed, but the exploitation remains the same.

For many Africans, this story is all too familiar. Kenya’s own independence struggle saw similar betrayals. Leaders who aligned too closely with Western interests thrived, while those who demanded full control over our resources and policies were sidelined—or worse. The tactics have changed, but the strategy remains the same. One of the film’s most fascinating elements is Jazz music. It is kind of a character in the political situation playing its own role. Jazz, born from the pain and resistance of Black people in America, became a tool for U.S. propaganda. The CIA used famous musicians like Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, and Duke Ellington as cultural ambassadors, sending them on tours across Africa, Asia, and Europe to promote the image of America as a land of freedom and artistic brilliance.

But back home, the very country that paraded Black musicians around the world was still enforcing segregation. The same America that spoke of liberty was overthrowing African leaders and propping up dictators. The irony is not lost in the documentary, and it should not be lost on us either. It made me wonder: How often is art used to distract us from the truth? And how many of our own African musicians, filmmakers, and influencers are unknowingly playing a similar role today?

One of the most striking figures in the film is Andrée Blouin.A woman!She is , Lumumba’s adviser and a fearless advocate for women’s rights. Her name is barely mentioned in history books, yet she played a critical role in shaping Congo’s independence movement.Johan mentioned that during his research, she is mentioned as a prostitute and thought that might be someone interesting to uncover and Alas! Blouin’s presence in the film reminds us of the many African women whose contributions have been erased from history. This erasure is deliberate, and films like this challenge us to dig deeper.

Soundtrack to a Coup d’État is not just a history lesson. It is a challenge. It asks us, as Africans, what we are going to do with this knowledge. We now understand how power works—how coups are orchestrated, how resources are controlled, how narratives are shaped. The question is, are we still allowing it to happen?Today, we don’t see assassinations like Lumumba’s as often, but we see economic sabotage, media manipulation, and political puppetry. We see African leaders signing away their countries’ futures in boardrooms instead of battlefields. The methods have changed, but the game remains the same. Watching this film felt like sitting through a long history lesson that had notes, clips, quotes and a whole album that summarized all I needed to know in a very digestible manner.

This is why we must tell our own stories. We must make our own films, write our own books, and sing our own songs—not as tools of propaganda, but as declarations of truth. Because if we don’t, someone else will do it for us. And history has shown us whose interests they serve.

Soundtrack to a Coup d’État is a brilliant, unsettling, and necessary documentary. It is a film that should be shown in every school, every university, and every home across Africa. Because understanding our past is the first step to reclaiming our future.

Soundtrack to a Coup d’Etat was nominated for the Best documentary feature category at the 97th Academy Awards. The film premiered at the Sundance Film Festival on 22 January 2024. It won the André Cavens Award for Best Film from the Belgian Film Critics Association. ( Source; Wikipedia)

It is still showing at unseen cinema, Nairobi, Kenya upto the 2nd of March. I implore you to go watch it.

The film scores a 9 out of 10.

Leave a comment